This is long, but if you care about the subject (including the drama about the numbers), I think you need to know it. I’ve been trying for six days to re-write this email that I sent to New Zealand friend David Grayson MD, but I can’t come up with anything better, so here it is. I’ve expanded it a bit with later news.

I love data, as regular readers know – I’ve blogged a lot here about COVID-19 data. The reason I love data is because of what we can learn from it. But if the data is erratic, chaotic, incompetent or corrupt, it’s like a bad road map: it might lead you off a cliff. And our COVID-19 data is beset with all four problems.

If data is erratic, chaotic, incompetent

or corrupt, it’s like a bad road map:

it might lead you off a cliff.

This data is all four.

Look, we don’t know how this virus behaves long-term: we don’t even have six months of data on it – the first known case was Nov. 17, just 21 weeks ago, and we only started getting serious about it in January, three months ago. We’re still learning.

So:

- I no longer assume the numbers match reality. They might be the best we have, and we gotta keep moving, but don’t be surprised if we later learn these early numbers were wrong.

- The number of deaths and cases are at least as high as reported, but we do not know how many are infected and not hospitalized because we’re not testing everyone. (Not by a long shot – see the list of CDC criteria in this article – just today – about a Texas woman with the disease who tried five times to get tested. (In the first hour there are 60+ comments on the article’s Facebook page, many saying “Me too!!”)

- Again: we only know what numbers have been reported. We know nothing about the great, great majority of the world.

- Thus, I no longer assume the forecasts (computer models) based on those numbers are correct. We literally have no way of knowing. (How good could a weather forecast be, or a sales forecast or a political poll, if it’s based on sloppy information?)

- Regardless, we must move on, even with fog on our windshield, because the virus is chasing us and we can either think and respond or just hide and hope. (Guess which I prefer.)

My email to Dr Grayson was about how I’m dealing with this:

David,

Just yesterday I read several pieces that altered my thinking about all this. I’m trying to think what to write about it.

One item was the latest episode of the “R!sky Talk” podcast (about risks, aka probabilities) by Cambridge statistician David Spiegelhalter. This episode’s about the virus data – 26 minutes: audio, transcript. (The audio is much more entertaining than the text.)

It’s convinced me that it’s absolutely pointless to infer or conclude anything from today’s numbers, EXCEPT their relative behavior (percent change), because without full knowledge of varying circumstances, comparisons among them are worse than meaningless – they appear to have meaning.

For instance I didn’t realize there’s significant variation in the definition of a COVID-related death!

- In some countries, no matter what happened, it only gets counted as COVID if the death certificate says that’s the cause of death.

- But in the UK, if you’re in a hospital with that diagnosis and you die, it gets counted as a COVID death, even if you died of something else; and if you have the virus but you die at home or anywhere not in a hospital, it’s not counted as COVID, full stop!

Then there’s the sad reality of when the numbers get really bad: total system breakdown. A friend in Spain told me on Facebook last month that their system is overwhelmed, with more sick people and deaths than anyone can cope with and more coming constantly. (NPR reported March 24 on a Madrid nursing home that had been abandoned, leaving dead and sick people behind.) The last thing on anyone’s mind in such a breakdown is making sure the statistics get reported. So, truly, we don’t at all know how many have died in such places.

Then there’s timing. Some locales report the number of deaths that happened each day; others only report ones they heard of that day. Some don’t report data on weekends – they save them up for Monday – but other places do, so the numbers don’t line up. Plus, Spiegelhalter says some places are prompt, while others report a couple of weeks later. With this virus, that delay throws things off by a whole two-week incubation cycle. In short, the reported numbers don’t necessarily reflect what happened that day.

So who knows how many people have actually been killed by this virus and when?? Nobody. (But it is meaningful to look for patterns. More on this in a moment.)

Additional challenges of building a model

In @Zeynep’s April 2 piece in Atlantic, titled “Don’t Believe the COVID-19 Models. That’s not what they’re for,” the paragraph on Wuhan lists a juicy bunch of variables to ponder if you’re trying to predict what might happen: (Italics are my comments)

- What’s the attack rate—the number of people who get infected within an exposed group, like a household? [Any computer model must have an assumption about this, to calculate how it thinks it will spread.]

- Do people who recover have immunity? [Just today, April 13, an epidemiologist wrote about this question.]

- How widespread are asymptomatic cases? [This is excruciatingly important: we have no clue how many people have the bug with no symptoms, because we’re not testing everyone. So how can we possibly know what percent of people with the bug get sick? We can’t.]

- And how infectious are they? [This too is extremely important: if someone you live with tests positive, are they likely to make you sick? We don’t know yet.]

- Are there super-spreaders—people who seemingly infect everyone they breathe near—as there were with SARS, and how prevalent are they?

- What are the false positive and false negative rates of our tests?

Dr. Sarah Markham, a colleague in the BMJ Patient Panel group pointed me last week to this surprisingly short piece in New Scientist, which summarizes the uncertainties very quickly:

Estimates of the predicted coronavirus death toll have little meaning.

With all the unknowns about COVID-19,

any numbers you hear about death tolls

or how long restrictions will last

should be taken not just with a pinch of salt but with a sack of it

It continues, aligning with Zeynep:

“We are living through a situation with few certainties. If someone calculates that 1 per cent of the global population is set to die in this pandemic … this could be wrong for at least six reasons.

- First, we can’t yet be sure of the fatality rate, or to what extent this will be affected by local shortages of ventilators [etc]

- Second, we don’t know what proportion of the world population is likely to catch the infection, with some estimates varying between about 60 and 80 per cent.

- Third, we don’t know to what extent national restrictions, which vary wildly across the globe, will prevent or delay infections and deaths.

- We can’t know yet whether we can slow the pandemic long enough to develop drugs and vaccines that can dramatically cut the number of COVID-19 deaths.

- Finally, we don’t even know what kind of immunity – if any – is conferred by this virus, and whether it is possible to develop severe symptoms from a repeat infection.

But not all is unknowable: as long as a country reports consistently, relative patterns are worth noting. Spiegelhalter says that in every country or region where an outbreak starts, in the early weeks it grows at 30%/week. Then you start to see the effects of different interventions.

Sweden and Norway – a “natural experiment”

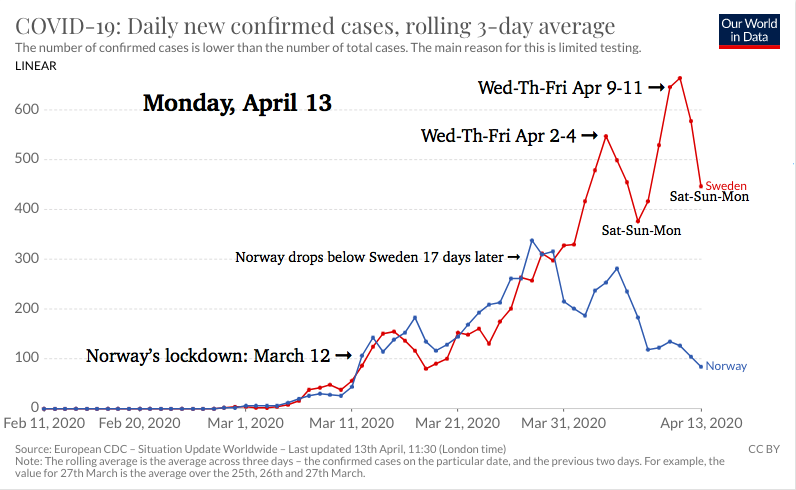

Spiegelhalter says an interesting natural experiment is underway: demographically similar neighbors Sweden and Norway have taken opposite approaches – Norway’s locked down, Sweden’s encouraging people to “act like adults” (see article below), knowing that there will be deaths and hoping that then they’ll have “herd immunity.” Here’s the OurWorldInData chart for new cases there, rolling 3 day average, as of April 7:

The Wikipedia page on Norway COVID says their lockdown measures started March 12, and surprise surprise, their numbers dived on the 29th – 17 days later. See? The numbers can’t tell us who does what differently in each country, but that 2-3 week COVID-19 cycle is evident. Useful.

Update: Here’s today’s edition of that chart – note the weekend dips, suggesting that Sweden doesn’t report on the weekend:

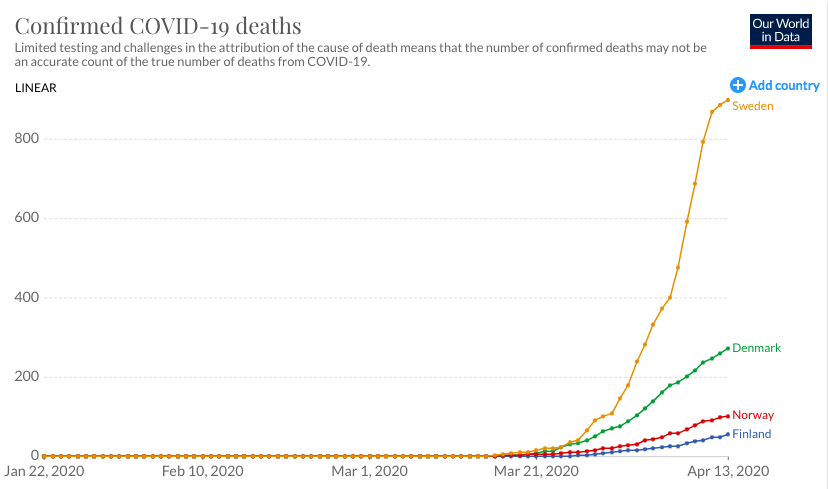

As I was writing this, EuroNews posted Is Sweden’s strategy working? including another chart. The charts above show the number of new cases per day; this article showed one for total deaths so far in Scandinavia. The numbers are tiny (hundreds) compared to the US, of course, but look at the relative growth, particularly comparing Norway and Sweden:

(Sweden’s population is about twice Norway’s.)

Beware the pseudo-experts

This item isn’t about the data itself; it’s about interpreting it competently.

Last Monday I did a complete about-face on Tomas Pueyo’s epic-length Medium posts, which I’d been admiring. I had been thinking “Holy cow, why haven’t more people been noticing this?” In light of the above, though, I wrote this on Facebook:

I’ve become suspicious of this fellow’s work, based on some deeper digging I did. Long story short, his thinking is quite interesting but:

a. He’s a video game magnate, not an epidemiologist – doesn’t really know what he’s talking aboutb. All his thinking (however good it might be) about the available data can’t change the fact that our data collection is quite spotty, inconsistent, incomplete, so there’s still no way to evaluate his assumptions, so there’s no basis for believing any of his conclusions(!). All we can do is think “Hm, that WOULD be something if everything panned out” – but the last thing we need these days is more baseless speculation (no matter how fascinating).

c. He’s a relentless self-promoter with a hired publicist. That’s not in itself a condemnation, but it’s fishy. [Indeed, unlike statistician Spiegelhalter, Pueyo asserts that his graphs are fact – a sure sign of a hustler, not a scientist.]

And then there’s corruption.

There are lots of ways to be corrupt.

When I was about 4 years old, one night I told my mom I was ready for dessert. Then I told her not to look under the table. (I’d sorta put my peas there, because I didn’t want to eat them.)

In a criminal trial you could bribe a judge, murder a witness, hide evidence. Science is about evidence, and especially with a killer virus, I don’t think anyone including a government should interfere with gathering evidence, nor should they suppress it. Authoritarian nations like China are suspected of hiding their real numbers. Corruption.

The US isn’t immune. How many people in the US have the virus? Hard to tell without testing. But a friend thousands of miles from me reports that after ten days with a 103 fever, unable to get tested, she did get tested and was quietly told that there’s pressure not to report a lot of cases, so we can get the economy rolling again.

Whoever does it, that’s corruption of evidence – corruption of healthcare – for political purposes. My friend also learned that during the time she was being told she wasn’t urgent enough to get tested, the hospital actually did zero tests in a five day stretch, then reported to the state that they had no signs of an outbreak.

It reminds me of how, when the cruise ship Diamond Princess (with 700 coronavirus patients) was visited in Japan by staff from our embassy,

….Deputy Consul General Timothy Smith told staff members that they would not be receiving tests in the embassy and instructed them not to seek testing from outside the facility despite their work with the cruise ship passengers. (Emphasis added)

American employees got within arm’s length of infected travelers and were not separated by glass or curtains while working with them. Those who then asked to be tested were told they must present symptoms, including a high fever, first.

That’s just plain stupid: the virus has an incubation period of up to 14 days, but they won’t let them get tested until they’re already sick?

Here’s why we do still need models.

Above I said “that WOULD be something, if it pans out.” That “if” jigsaws nicely with a point in Zeynep’s article, about the statistical prediction models: governments must have them, to understand the range of situations we might face in the predictable future. By trying all sorts of assumptions you an answer “What’s the worst that can happen?” and “What’s the best,” and everything in between. This lets you plan ahead.

As Zeynep says, the right way to use a model is to run it with certain assumptions, spot the disaster scenarios, and backtrack to see how they turned bad. That way, you know where to invest effort.

New Zealand shows the value of learning

As I told my friend Grayson in that email last week,

An important factor for Kiwis is the tremendous value in not being a “first mover” when a new bug shows up whose behavior is unknown.

It’s another reason to slow the spread – to harvest as much experience as possible from the rest of the world’s approaches, before being forced into doing it. The virtue of behind the times, as you say, to see how different strategies play out.

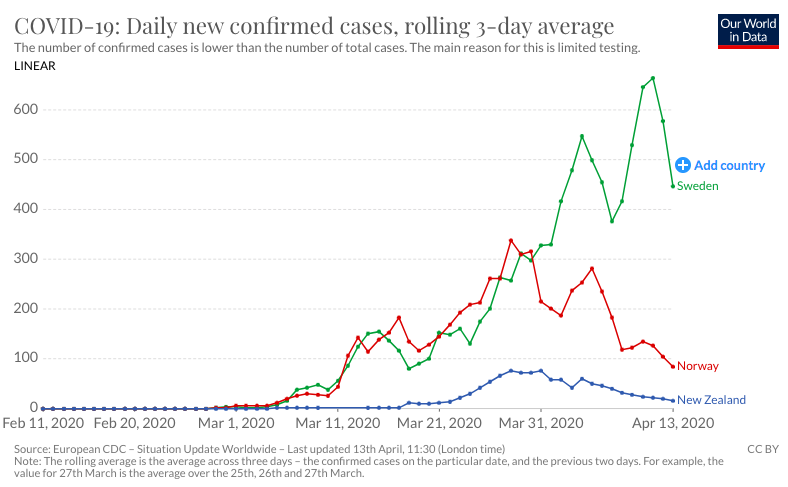

They seem to be doing fairly well at it. New Zealand’s population is a bit less than Norway’s, and their climb started about three weeks later – see how it’s playing out for them, with tough measures from the beginning:

As the Post said last week, New Zealand isn’t just flattening the curve. It’s squashing it.

Keep doing what works. Stay safe, stay clean. And remember – as ZDoggMD said to his daughter, “The remedy for anxiety is knowledge and preparation.”

p.s. Remember – all the above trends may change, the next time we look. All we can know for sure is what numbers have been reported so far.

You very correctly point out assumptions that modelers needed. Is there any public information on the values for these assumptions used in these models? Or even models that could can used on line?

All I know is that there are many models, and I haven’t heard of any publishing their assumptions. It would be great to discover one!

Excellent, useful analysis of the numbers and assumptions dominating public policy and public opinion around the world.

Excellent piece Dave. I’ve concluded that we just don’t know, although we do have the NYC v SF, UK v Ireland, Sweden v Norway “kinda matched pairs” experiment. But anywhere not taking the Taiwan/Korea/Singapore approach is destined to have a lot of deaths/morbidity.

We only know 2 things for sure.

1) We know NOW what an overwhelmed hospital system looks like. As Trump says 20-60 thousand people die of the flu each year, but that never overwhelms the hospital system of NYC, Madrid, Lombardy, Detroit, etc.

2) When this is done and we eventually count ALL deaths we should know the real “COVID19” death rate, which is the difference between actuarially expected deaths v actual deaths. We hear that there are 2,000 Covid deaths per day. Roughly 7,000 people die per day in the US. Is that number now the same (i.e Covid deaths are replacing others) , 9,000 (i.e these are additional deaths) or even more (there are deaths we are missing like that nursing home in Spain). Your piece makes clear that we don’t know

Very happy to hear that your famously picky self finds this on target!

Dave, you need to look at https://aatishb.com/covidtrends/

Which is ALL relative, new cases vs cumulative cases, or if you want better, new deaths (easier to count) vs. cumulative deaths. It’s a unitless value that behaves the same way to show where a nation is in terms of control. It is simply based on the fact that the derivative of an exponential is an exponential, and well known population biology about the fact that exponential growth cannot forever sustain.

Another story of corrupting the process, to go along with my 4 year old “hide the peas” story …

In the 1980s I drove to New York City for a customer meeting, then went to watch my sister sing in a cabaret. When I came out around midnight I found my car had been broken into and the trunk contents stolen.

I drove home, arriving around 3 a.m. The next morning I called the local precinct to report the crime … and learned that they won’t count it unless you come in and fill out a report yourself. Can’t mail it in, etc etc.

In an amazing coincidence, this was during the era when there was political pressure to reduce NYC’s crime statistics.

A physician friend in Arkansas posted on FB:

“A home that I’m aware of here did a “pilot” test of all patients and staff and had 38+ patients and 17+ staff, nobody was sick. They decided not to test the rest of the homes!!!!”

Anyone want to put any stock in the reliability of statistics on case and deaths there?