I’m participating today as a “consumer/patient” voice in a meeting on clinician burnout, part of a project of the National Academy of Medicine. I was going to be there in person but a bad and contagious coughing cold kept me home, so I’m watching and listening remotely.

Remote participants often don’t get as much chance to speak up, so I’m doing what empowered people do: find another way to get heard.:-)

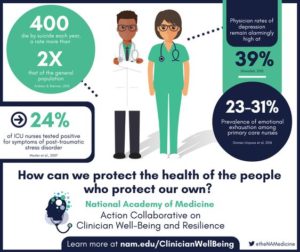

Burnout is important to me, because I’m deeply grateful to the highly trained people who saved my life 11 years ago, and I want them to have a good life. But look at the statistics in the project’s infographic here. It drives me nuts (and makes me sad) that the doctors and nurses who put in all those years of training, and gained their years of experience, are so often unhappy with their working life.

Four hundred physician suicides a year in the US?? One every day?? As a co-founder of the Society for Participatory Medicine, this is just not acceptable. We must change the system. That’s what this NAM project is about. (Dive into the project website, if you’re curious about the depths of this problem and the research that’s being done to fix it.)

Four hundred physician suicides a year in the US?? One every day?? As a co-founder of the Society for Participatory Medicine, this is just not acceptable. We must change the system. That’s what this NAM project is about. (Dive into the project website, if you’re curious about the depths of this problem and the research that’s being done to fix it.)

Here are things I would have liked to say in this morning’s session.

1: Usability of EMRs

Background for my readers: A big focus is the problems caused by the introduction of electronic medical record systems (EMRs). The problem isn’t the existence of computers – it’s that the initial wave of them is widely said to be incredibly hard to use. One study cited today says it takes 4,000 clicks per day for one clinician’s work. (In an 8 hour day that would be 8+ clicks per minute, all day long, in between actually engaging with the patient.)

Feedback 1: Please – follow the lessons learned by aviation years ago. As more data was fed into the cockpit, pilots became overwhelmed and crashes increased. This illustrates that the precious asset is not the information, it’s the pilot’s (clinician’s) attention. In our current generation of EMRs this is a disgraceful mess. We must insist that vendors improve how well the system draws everyone’s attention to what’s important. (One speaker aptly described it as “information clutter.”)

When we achieve more clarity in the presentation of chart contents, I’d bet my house that we’ll have a reduction in medical errors caused by important information that was missed in the clutter.

Feedback 2: The elephant in the room – vendor resistance to usability. In 2009-2011 I was part of several meetings and workgroups on the introduction of electronic medical records. Enormous amounts of money were at stake- tens of billions – so there was a years-long rugby scrum, with elbows being thrown everywhere as people jostled to influence the rules about which systems would qualify for all that juicy money.

This was a critical moment, and we blew it. Numerous voices testified that if the systems weren’t usable, doctors would hate them. (Sound familiar?) Meanwhile, it was whispered in the back halls that at least one powerful vendor CEO (unnamed) said “Usability will be a criterion over my dead body.”

In June 2010 I was invited to speak at a meeting of IT people related to AHRQ grants. I titled my speech “Over My Dead Body”: Why Reliable Systems Matter to Patients.” That link goes to my blog post about that speech, with links to video and slides.

We lost, the CEO got his/her way, and clinicians everywhere are suffering as a result. We must not keep stepping around this elephant; it’s there and we can’t ignore it, so we need to explicitly deal with the consequences of that decision in the certification criteria. Which brings us to …

2: Scribes

For my readers who don’t know, a “scribe” in this context is a “helper” who sits off to the side and takes notes in the computer about what the clinician is doing. Of course these are skilled people so they’re not cheap, but they save the doctor’s mind and improve care. (One speaker noted that in a four-hour half-day, they saved 1.5 hours of doctor time! Another noted that patients reported much higher satisfaction when the doctor or nurse paid full attention to them.)

I want to be very clear here: this is the near-disaster that we bought ourselves when we rejected usability as a concern. Now we must, one way or another, buy our way out of the problem, because right now we’re paying for it with lower patient satisfaction and increased clinician stress. That’s horrible way to move medicine into the computer era.

Some in the discussion today complained that scribes cost money. The more appropriate way to look at it is that bad usability costs money!

3: Participatory medicine

Finally, I am grateful to have been invited to this meeting, and hope my thoughts will be a real contribution. I encourage the Academy to view this issue as a chance for patient/clinician collaboration, which our society calls “participatory medicine.” The usual paradigm is that patients and clinicians are separate, non-overlapping parts of the health system, but many of us are truly eager to help improve care.

In this spirit I submit two resources for consideration.

- The OpenNotes movement lets patients read their clinicians’ visit notes. 20 million US adults now have access to this opportunity. I’m one of them, and I’ve personally experienced how it brings me closer to my care team.

- The latest study, currently in process, takes it to another level: OurNotes, in which patients contribute as co-authors of parts of the chart. Watch for its results when they’re published.

- A wonderful new book this year by Mayo endocrinologist Dr. Victor Montori calls for “careful and kind care.” It consists of numerous stories in which “careful and kind care” was impeded (or simply failed) for various reasons: finance, EMR, time pressures, and more. The book is titled Why We Revolt. I know Dr. Montori, I know his heart and mind and character – he cares deeply. Importantly, when I read the stories I thought not just of how care was falling short on the patient’s side, but how most stories also showed the clinician being impeded by all those factors.

Thank you again to the Academy for inviting me. I hope this shows that patient voices can have many things to say, many wishes to contribute to improving care.

Why would we? Because we value our clinicians and want them to have a great life, as their just reward for the years they put into education and clinical experience.

Thank you for explaining a good deal of new and interesting information to me.

How do we get doctors to take part in Open Notes?

What about when we, the patient, sit in ER’s, as I and also my elderly parents have, wishing there was EMR instead of waiting for hours for the hospital to take new tests because they have no record of the same test we recently took at another facility?

Thanks for all you do. It is greatly appreciated.

Cathy Chester

Cathy, your simple requests are classic examples of why the OpenNotes movement is important. Thanks for asking them.

> How do we get doctors to take part in Open Notes?

1. Ask for it, over and over.

This is change, and change starts with speaking up: telling the people in charge what you want. If you don’t, then later they often say “My patients aren’t asking for this.” So ask, and ask again. It’s best not to be obnoxious, but be clear, and explain why it’s important to you.

Suggest to friends and other patients that they ask, too: “Just google Open Notes and you’ll see the website. It has lots of information for patients and for doctors about how to do it.”

Usually it’s not up to the individual doctor – be sure to give this message to the people in charge, as I say – the practice manager or whoever. If they send you a feedback or ratings form, mention it again.

2. Learn more about it, so you can tell others. The OpenNotes website has lots of useful pages for different people. On the For Patients menu, for instance, is a Notes & You page.

3. Tell others. This is exactly like other social change movements; it’s up to us to spread the word. (There’s good news in this case: after years of experience, 20 million US patients now have access, which means the initial resistance has been overcome – we can now point to that success when we ask others to get on board.)

_________

> Waiting hours for them to take new tests

First, note that test results are available WITHOUT OpenNotes: every provider is required to have a “patient portal,” which must let you see your lab results. So wherever you got those tests, you should be able to get them. BUT, YOU have to get them and organize them, and they often don’t tell you about your rights to get a copy (or even that they have a portal where you can see them!).

The expense and wasted time of unnecessary tests (including scans that expose us to extra radiation!) is one compelling factor for avoiding duplicate tests. But this one doesn’t require that they use OpenNotes – you already have the legal right to the results of every such test.

But, as I said: (a) you may have to ASK for it, and (b) it’s up to you to get them, organize them, and store them. This takes work, but nobody else (in the US) is going to do it for you, at least not today. In our Society for Participatory Medicine we certainly want that to change: we want healthcare to empower US to manage our care, by making it easy to organize our information.

Meanwhile, there are apps and websites that do their best to gather the information. A list off the top of my head of some that I know:

– CareSync

– Hugo PHR

– Zibdy Health

– Carebox Health

I just googled ” and found

this random page, which seems interesting. I haven’t vetted it, and I encourage you to go looking for what best suits YOU.

In any case it sounds like you’ll find value in the OpenNotes site’s Ten things patients can do page.

Thank you for speaking up – these notes I collected are useful and should probably be a page on this site.

Slapping my forehead – I forgot to mention the most obvious: go plunder the excellent site Get My Health Data. (Sounds relevant, eh???) The page at that link has a list of DOZENS of apps. (I didn’t realize they’d done that, since I spoke to them last!)