Important update next day: see comment below by Michael Porembra (and my reply) with new source information and important data on changes in rate of adoption.

Important update next day: see comment below by Michael Porembra (and my reply) with new source information and important data on changes in rate of adoption.

A tweet from South By Southwest by @DVanSickle led me to finally post this, which I dug up last spring with the help of the ever-awesome @TedEytan of Kaiser. It’s part of my presentation at the Kanter Family Foundation’s confab last May for their Learning Health System initiative. (Video of that speech is here.)

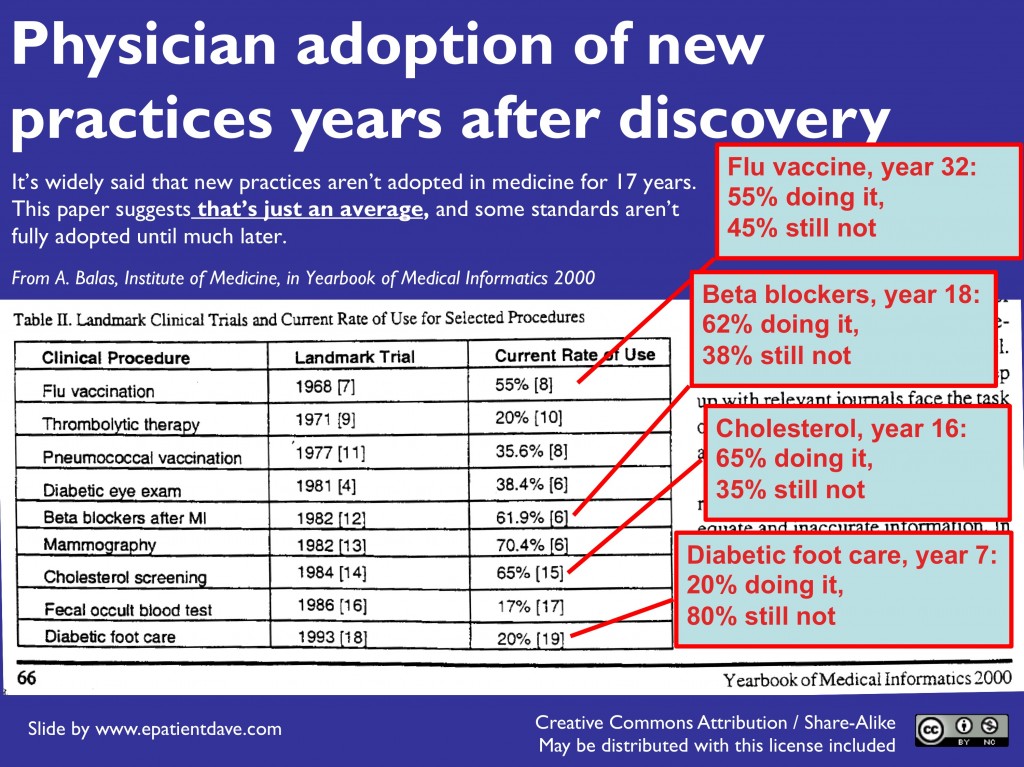

The issue is a statistic often quoted by advocates for improving medicine: “On average it takes 17 years for new practices to be adopted.” That’s pretty shocking – the idea that some docs may not know something important to your college-age kid, even if the info came out when that kid was in diapers!

The source turns out to be a paper published by the Institute of Medicine in their Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000. I’ve been unable to locate the full text online; somebody (Ted?) emailed me a scan, from which I screen-grabbed the excerpt in this slide.

For more validation, here’s a Google search of the table’s title, and here’s a search of “Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000″+Balas.

People always ask “Is it still true?”

I don’t know of an update – if you do, please add it in a comment! See important update to this in comments.

But I’ll say this: people are pretty much in denial. They asked the same thing about the IOM’s 1999 report “To Err is Human” (the report with the famous statistic “up to 98,000 accidental deaths a year in US hospitals”), saying “Things must have improved since then.” But every single paper I’ve seen on the subject has said the rate of fatal errors (and serious non-fatal ones) is no better today.

The truth is, things like this are system problems, and system problems don’t go away spontaneously – you have to address the systemic issues, or things stay on track, just as if they had a gyroscope. Update: I now say this observation has to be paired with the trend in the comment below.

But an important reality is that doctors (at least in America) are often burdened with enough work that it’s hard to keep up. (The average primary physician in the US has 1500-2000 patients, according to Paul Grundy MD of IBM. Imagine how many conditions they’re supposed to stay current on!) That’s why my TEDx talk ends with the chant:

Let Patients Help!

To me this is yet another example of how empowering and informing patients can improve medicine at very little cost.

I say: we need a website StandardsOfCare.org, and we need to tell every patient and caregiver to look there: “Know your standard of care. Bring it to your doctor’s attention.”

I acquired the domain last year. Anyone want to create a project to populate it??

I vote Tammany-Hall-style (early and often) for the StandardsOfCare.org website! Is that an SPM initiative in the birthing process, one that we could seek foundation grant $$ for … ?

I don’t care who does it, as long as someone does. Let’s spread the word!

Shocking and fascinating at the same time. Love the website idea. How about submitting it to kickstarter or indiegogo?

17 years is not too bad, considering how long it took the British Empire to implement practices to conquer scurvy. The entire article is a good read:

The Healthcare Singularity and the Age of Semantic Medicine

…The total time from Lancaster’s definitive demonstration of how to prevent scurvy to adoption across the British Empire was 264 years.

This article references the study re: 17 years for adoption of practices today.

THIS IS IMPORTANT – gotta run, but I’ll blog about it later – some quick notes, and especially see the final point about change –

__________

Michael, that’s a goldmine! This is the most important discovery (for me) in a long time.

I’ll paste in more:

“The translation of medical discovery to practice has thankfully improved substantially. But a 2003 report from the Institute of Medicine found that the lag between significant discovery and adoption into routine patient care still averages 17 years [3, 4].”

[3] E. A. Balas, “Information Systems Can Prevent Errors and Improve Quality,” J. Am. Med. Inform.

Assoc., vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 398–399, 2001, PMID: 11418547.

[4] A. C. Greiner and Elisa Knebel, Eds., Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality.

Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2003.

and:

“This delayed translation of knowledge to clinical care has negative effects on both the cost and the quality of patient care. A nationwide review of 439 quality indicators found that only half of adults receive the care recommended by U.S. national standards [5].”

[5] E. A. McGlynn, S. M. Asch, J. Adams, J. Keesey, J. Hicks, A. DeCristofaro, et al., “The quality of

health care delivered to adults in the United States,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 348, pp. 2635–2645,

2003, PMID: 12826639.

____________

I agree, it’s a phenomenal article – I can’t believe it’s never popped up in our discussions!

[3] is a new citation for Balas, in JAMIA – but there he points back to his earlier article, where, at last, we find the original study: “Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing Clinical Knowledge for Health Care Improvement. Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000: Patient-centered Systems. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer, 2000:65–70.”

Now to see if we can get the full text – I couldn’t find it out in the open.

IMPORTANT: The graph on the 4th page of Michael’s PDF shows there *is* a steady improvement – over a period of centuries. The last data point is in the 1980s, but the trajectory seems undeniable. And this subhead, on the previous page: “Could knowledge adoption In healthcare become nearly instantaneous?”

Look forward to checking out the new reference. I found some specific case studies that suggest rate is quickening (for better or worse). This study, for example, looked at stent diffusion and payment policies and suggests much shorter adoption cycle. http://bit.ly/13Qpgg2

Agree, David. The question for e-patient families – with a sick patient in a specific situation today – is whether THAT clinician has the needed info. 98% adoption can still be a disaster for the case that doesn’t have it.

I’m all for system improvement of course! Meanwhile, that’s no substitute for the patient & family (and community) being as engaged as they can, and for providers to listen & welcome it – to do the “Let Patients Help” thing.

Perhaps the cycle is shortening as suggested by commentators. But that does not negate the value of getting everyone involved in their own health care, a precept I have championed for a long time. I have been looking for someone who agrees with that precept that will consort to produce the website. However, it will face significant legal push back from the industry.

Tom, what makes you think that having StandardsOfCare.org would negate the need for patient engagement?

Dave,

what are your goals for the website? Is it supposed to cover all of medicine or just a few diseases?

Gilles, I have no thoughts other than: doesn’t it make sense for someone to be able to find OUT their standard of care? I don’t care where… just needs to be credible / reliable with sources documented, so docs find it credible AND so e-patients can tell when the literature’s out of date (e.g. RCC).

It’s interesting the reaction I’ve had from the establishment. While it’s the establishment that says “docs only prescribe the standard of care half the time,” LOTS of docs (including high-ups) say “Well, the standard isn’t always the right thing to do.” I can imagine that, but no wonder we have wildly mixed methods & results, huh?

Dave you touched on a topic dear to my heart!

Let’s forget about RCC & cancer, at least for now,, because the degrees of complexities associated with contemporary oncology make it quasi impossible for anyone to keep a standard current. Without standard of knowledge you can’t have a standard of care that means something.

For many other diseases, where standards of care do exist, your idea is excellent. But it requires a network of expert volunteers willing to put many hours to build, for each condition, the models of care & knowledge. And then to keep these models current. It’s hard work to do. I am aware of a few efforts to do just this, in specific domain areas and know that, in each instance, the resources necessary are far beyond what an individual can do well over time. The best example I know, BTW, is the remarkable work done by C3N (see http://c3nproject.org/ )

Agreed – C3N is excellent and the army of volunteers is a big deal issue.

BUT – I suspect there are some no-brainers, perhaps the top 100 obvious not-so-tricky things where there’s NO disagreement that the patient should get X. Inspect a diabetic’s feet; baby aspirin; that sort of stuff. Any patient, not just tricky-cancer patients, should ideally be aware of any universally-agreed “shoulds.” Si?

I agree that it is distressing that it takes so long for new knowledge to become common knowledge and the basis for clinical decision making, but I think we should not be blind to the potential unintended consequences of a StandardsofCare site.

Many putative standards come from ‘guidelines’ that often represent opinions based on incomplete and provisional information. It took a decade to get JNC-8 after JNC-7 for hypertension, and JNC-8 says that beta blockers are not appropriate agents for hypertension because, while they lower blood pressure, they do not prevent bad cardiovascular deaths. But they made this decision based on limited data from a very limited and not-representative selection of beta blockers and dose regimens, probably not applicable to current options.

There is also the issue that these guidelines and standards are, by nature and design, aimed at a moderately mythical typical patient, and never take patient values, preferences or context into account.

The down side, then, could be ‘standards’ that patients misinterpret as Truth.

The up side would be that – properly done – it could mean my patients help me help them by coming in with new information, suggestions about care, and interested in hearing about how the information applies to them.

My strong vote (like Casey, early and often) is to do this because I think the potential benefits far, far outweigh the negatives.

Peter, thanks for posting this – in the time since this post several people have said things of that sort. Might be good to chew on it a bit.

It seems to me that the core issue you cite is that the truth shifts through time, not to mention which truth is relevant from patient to patient. (Consider the lovely book The Half-Life of Facts!)

I’m sure that you, as a wise and experienced physician, take many things into account in each patient’s case. I’ve heard numerous tales of that being true of other docs who also happened to be out of date, due to the flood of new information. (And that’s not to mention the constantly shifting guidelines from various agencies: Do get a physical! Don’t! Do get a mammogram! Don’t!)

My suggestion for a resource that’s readily available to the public was born out of the desire to have something ordinary people can get at. Perhaps every listing would need to come with a “Warning! This may have changed in the past week! And you might be different!”

At some level I just HAVE to believe that in the long run it’s not just good but IMPORTANT for ordinary citizens to know (a) the best advice does evolve, as science progresses, (b) it’s no massive indictment of a physician if the truth in one of their thousands of diseases has evolved, (c) patients can help – it’s quite reasonable, (d) it IS an indictment of a clinician if they’re in denial about this after it’s pointed out to them.

And that to me makes the case for teaching physicians those points …. and getting to work on some sort of formal (but manageable) tip sheet for ordinary-citizen e-patients.

Maybe even dancing lessons for both sides of the doctor-patient tango!

I hope I was clear: I enthusiastically endorse the idea, but I don’t want people supporting this without realizing that science is a messy and erratic journey towards temporary best-we-can-do-for-now truths. I agree that the messiness and constant change are fantastic reasons for clinicians (like me) to enlist patients in the effort to find the best paths and avoid the pot holes.

I wonder who will have more difficulty with this, patients or clinicians….

Who’ll have more difficulty? As in dancing, I’m sure toes will be stepped on and apologies will be issued. And as in dancing, when there’s a shared commitment to getting better at it, good things will happen.

Great idea. My daughter’s birth defect has no SOC and interventions vary wildly in the United States. Outcomes are largely dictated by the independent skill sets of the receiving physician or team of physicians. Current common practice in the US is not the SOC in England or Europe. We are talking about Pierre Robin Sequence, a triad of anomalies including a recessed lower jaw, a retro often large tongue and a complete bilateral U shaped cleft palate. Incidence is 1 in every 20-40,000 births. These babies often struggle to breathe and swallow. The e-patient community contains more information about this complex condition than may be found in any other source. Parents in the e-community refer struggling Moms and Dads to providers who will at least keep the child alive. Too often, children suffer life long issues due to failure to treat appropriately at birth and subsequently. A child’s care may vary considerably with drastically different outcomes even within the same facility! A SOC and guidelines based on presenting and continued severity of the condition along with information regarding common long term issues is desperately needed! Where do we sign up?!

This is a much more complex issue than most think.

The clock is almost always started retrospectively: when a new discovery begins to revolutionize care, we look back and think, “When was that discovered?” Rarely does the community recognize these great ideas when first presented. This is a misleading approach, because it conflates the process of scientific acceptance with process improvement in clinical operations. For example, adoption in clinic of an innovation in year 1 (rather than 17) would be risky. The FDA typically requires two clinical trials that demonstrate the intervention works, and we should probably start the clock after these.

Thus, a much better approach would be, “When was this confirmed?” A great paper (pubmed) demonstrates that in highly-cited (over 1000 citations!) papers claiming to have proven an intervention was effective, less than half of these were subsequently confirmed. (14 were either contradicted — patients where actually worse when the intervention was attempted — or found to not be as effective as reported.) It is absolutely critical that an independent team confirm the findings before we think about making standards about them.

Second, often a separate group is required to turn these discoveries into something that community-based physicians can deliver to their patients. Most new therapies are developed in specialized settings — subspecialty clinics or in specific populations and funded by grants, not insurance. We do not have any system that focuses on how to translate findings from subspecialty settings into general medicine. Several initiatives have focused on this — the Northern New England Cardiovascular Study Group, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and my own project at the National Parkinson Foundation — but even these have focused more on translating expert insight across expert clinics, less about getting them into general care settings.

Any good “standards of care” approach must (a) track outcomes over time and (b) focus on the standard of care for the typical case plus the indications that specialist/subspecialist care is required (science of care vs art of care). As complexity rises in medicine, it is naive to imagine that there can be one standard of care across settings. I did an analysis (presented on parkinson.org) that shows that for one drug, limiting it’s use provides benefits up to a point, but the very best care comes when that drug is incorporated into patient care by a leading expert: there is a “u-shaped curve”, where use of the drug is associated with the best and worst outcomes.

Maybe in 17 years, most doctors will be able to deliver those best outcomes, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

If you wanted to make a difference in clinical care, let’s start the “Foundation for Confirmation of High Impact Findings” and ensure that things that matter can get the funding required to become the topics of standards!

Hi Pete – love to have you here. I love the idea of “confirmation of high impact findings.” I assume you’re talking about the issues of research that’s never been verified, right?

If that’s what you’re talking about I’ll seed the discussion here by grabbing links to that topic’s posts on e-patients.net. The one that may harmonize with your idea is this one, about the Reproducibility Initiative in Palo Alto. Do you know its founder Elizabeth Iorns?

AND I wanted to say that I just re-read your comment above this, more carefully, and it’s a whole freakin blog post itself!

The public (and probably many docs & researchers) need to be educated about the problem of papers that are widely cited (and therefore considered credible), which later turn out to be weak, sometimes because they were weak in the first place (never replicated, as you say) or simply because new information came along. For instance, there’s nothing in PubMed that marks an article as “Overturned later,” “Has been validated 3x,” or anything of the sort, right? So if someone WANTS to know that, they have to go hunting on their own, yes?

The culture of science is about new discoveries, not firm foundations. And I’d say informed patients are pretty darn interested in firmness, moreso than wobbly new stuff.

Reading the thread on the topic of “17 years” I reached e-patient Dave’s December 1, 2014 at 10:51 reply. It may have been written over a year ago but better late than never I want to say that’s brilliant! Firm foundations underpinned by infomed updates, “Overturned later,” “Has been validated 3x”, how absolutely sensible, logical and necessary.

However, it is likely a distant dream as we are trying to survive in a system where the Lancet hasn’t even retracted a paper found to be fraudulent (Chandra R K (1992). Effect of vitamin and trace-element supplementation on immune reposnse and infection in elderly subjects. Lancet, 340: 1124-27.)

It is all very disappointing.

Thanks, Lynn. In such times of (often jaw-dropping) disillusionment I find it useful to remember something a wise person taught me years ago about transformation:

“The truth will set you free. But first, it will piss you off.” :-)

In awareness there is power. Can’t transform a problem we don’t know exists!

That is very true. With so many known problems in academia and medicine the awareness is a great weight. Sadly those who have permanent positions are frequently not concerned and will persist with 4* journal publications as a goal.

Dear Dave,

I wrote to you from my newly created Twitter account @Your_Advocate asking to discuss your “Standard of Care” idea. I have a strong interest in creating a website to help patients fight their commercial and Medicare insurance denials. Having a research area within the site that allows patients to understand their treatment options feels like a natural fit to this content.

I have looked into creating a 501C3 and want to offer help to people free of charge. I have a lot of experience in the medical device field and have been working as an advocate and marketer since 2007.

Do you have the time and inclination to discuss this further?

Best regards, Catherine

Hi Catherine – sorry for the long Thanksgiving delay in releasing your Nov. 21 comment! I know I asked you on Facebook to come post this here, but it ended up not in this thread – it was over on my Boards & Awards page for some reason. Anyway, I moved it, and here we are.

I’m no expert on creating non-profit organizations so I can’t advise you on that, other than to say that MANY people who’ve been there have said it’s a PILE of work so you really need to think about who will do all the work and raise the funds etc. Everyone said to think about why all that extra work is needed, compared to just doing it yourself. Or finding another org that might host it, like the National Patient Safety Foundation or SPM or someone.

This thread, though, is touching on other important issues that such a project will confront – I’m going to post another comment on that now.

Hi Dave,

I have had some time to research 501C3’s and reached out to a couple of friends that would be well suited to serve as a board member. Yes this is a giant endeavor and despite all of the work and financial investment, this is serving a higher cause and a much needed one. I will focus on what I know first (patient appeals) then see about incorporating a database that allows patients to share treatment information. The name “standard of care” I don’t think really fits here with the concept simply because it reflects a very conservative approach to medicine.

I will keep you apprised with my progress!

Best regards, Catherine

Still looking for the full text? Here it is including citations for the source of the data:

https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/pdf/10.1055/s-0038-1637943.pdf

Thanks, Mike! Great to have contributions years later – the conversation goes on.

How did you end up coming here?? What seeking brought this up?

Do you know of any updates?